If you have been keeping abreast of the news lately, you might have come across a news story that highlighted a recent study published in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM), which found that salt consumption wasn’t associated with an increase in systolic blood pressure in either men or women, after controlling for factors like age (1). Given that health authorities have been saying for years that salt increases the risk of hypertension, these recent findings are another wrench in works for low-salt proponents.

This is not to say that very high salt consumption is safe. There is good evidence that reducing salt intake from 9-12 g per day, in large part from eating junk food and prepackaged foods, to less than 7 g per day, does promote a significant fall in systolic blood pressure (2). The problem is getting a handle on what exactly this means, particularly when these same changes seem to have no effect on lipid levels, and the risk of dying from cardiovascular disease is at best weakly associated with high salt consumption (15% increase in risk). Once again, as I addressed in an earlier blog, we need to make sure that we don’t confuse our objectives, and remember that hypertension isn’t so much a disease as it is as diagnostic sign. Just because we can alter the findings of one diagnostic sign through various interventions, doesn’t necessarily mean that we have altered the course of the disease. It is really just another example of failing to see the forest for the trees.

Despite these rather unconvincing findings, authorities continue to suggest that we’re consuming too much salt, with the US Food as Drug Administration (FDA) suggesting that we consume less than 2.3 grams per day, and the American Heart Association (AHA) going even further by recommending that we consume no more than 1.5 grams. After all, if eating too much salt is a bad thing, dramatically reducing our consumption must therefore be a good thing – right?

Nope.

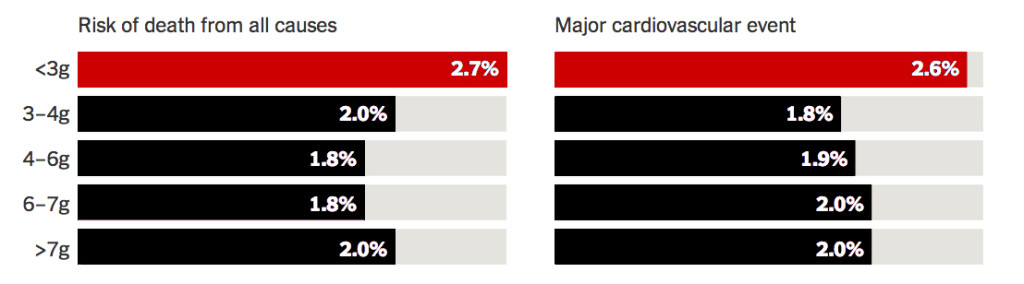

In another recent study published by the NEJM (3), researchers compared the health outcomes of patients that followed the very low sodium diet recommended by the FDA and AHA, consuming less than 3 g per day, and found that they had a higher risk of death or cardiovascular than those who consumed more than 7 grams per day:

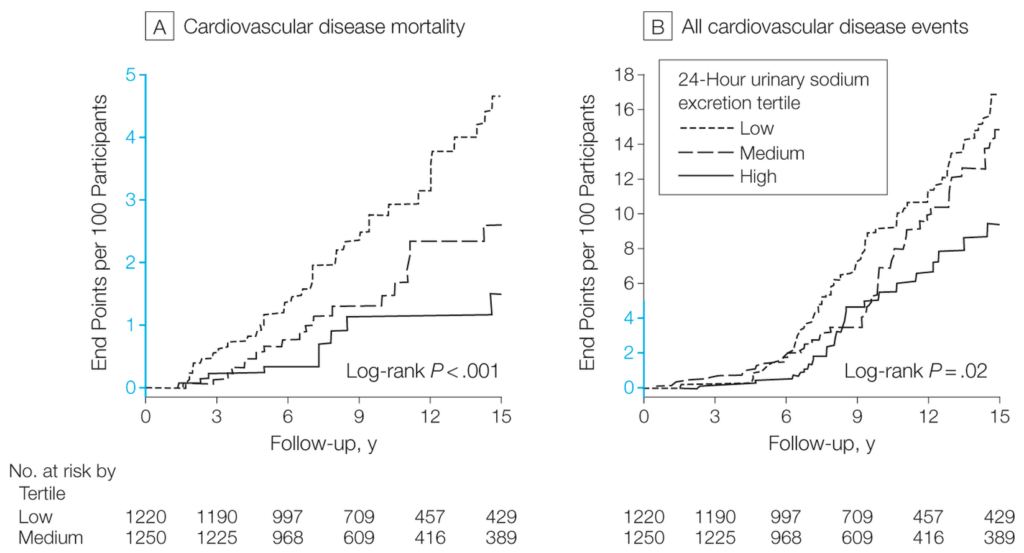

Shocked? You shouldn’t be, because it’s not the first time we’ve seen these kind of results. A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2011 found much the same thing, after following 3,681 people for almost a decade that were eating either a low, moderate, or high salt diet (4). And while researchers again found that excessive salt intake was associated with an increase in systolic high blood pressure, they found that a low-sodium diet was significantly associated with higher mortality from cardiovascular causes:

According to the USDA and Health Canada, the average North American consumes only about 3.4 g of salt on a daily basis, which according to the latest research, suggests that most of us are consuming salt at the low end of the spectrum. Personally, I found these results surprising, especially considering just how much prepared and packaged food we eat, which is notorious for containing the high levels of salt which appeals to our tastebuds, activates our appetite centre, and stimulates impulse purchases. But it seems that even with what is still perceived as relatively high salt consumption, most of us are eating salt within a range that is associated with the least risk. Besides which, we’re talking about very small differences in risk, regardless of how much salt we eat. There are far bigger fish to fry, for example, when we compare the effects of eating too much salt, to the consumption of a high carbohydrate diet, which increases the risk of diabetes by 44% and the risk of CVD by 25% (5).

In Āyurveda, salt is a flavor that is an essential part of the diet, and to help maintain good health. Salt stimulates the appetite, promotes the flow of glandular secretions, and assists with the assimilation and absorption of food. It is described as viṣyañdī, meaning that it promotes tissue secretion, and sūkṣma, because salt opens the channels and promotes the easy passage of the feces, making it helpful in constipation. Salty flavor is hot, heavy and wet in quality, and helps to reduce and balance vāta, the component of the humoral theory in Āyurveda that is most closely associated with function of the nervous system. Sodium accounts for almost half the osmolarity of the extracellular fluid, playing a key role in conducting electrical impulses throughout the body. With excessive sweating or diarrhea, the loss of sodium and other electrolytes disrupts the function of the nervous system, leading to issues including nausea and vomiting, headache, mental dysfunction, fatigue, irritability, weakness, cramping, seizures, and loss of consciousness. Often people will think to drink water when they’re dehydrated, but without the addition of electrolytes such as sodium, the water will go right through them and the problem will likely get worse. Although medical organizations like to suggest oral rehydration packets loaded with sugar to restore electrolytes, research has shown that a traditional Āyurvedic salted rice soup (e.g. peya) is far more effective (6).

While I am an advocate for consuming salt, like anything, there is a down-side too. Apart from the overt effects of hypernatremia, which is almost impossible to achieve from dietary consumption, the excessive consumption of salt irritates the mucous membranes, and can lead to inflammation. In a similar fashion, excessive salt weakens digestion and promotes congestion, leading to a feeling of heaviness and lethargy. In this way, salt consumption is limited in kapha (congestive) and pitta (inflammatory) conditions in Āyurveda, but even with these contraindications, it is never eliminated entirely.

Perhaps the most important issue to consider when it comes to salt is the source. Most commercial sources of table salt are prepared from pure sodium chloride, to which various ingredients are added, including anti-caking agents (e.g. sodium aluminosilicate), and if the salt has been iodized, the addition of alkalis (e.g. sodium carbonate) and stabilizers (e.g. dextrose, sodium thiosulfate). I don’t recommend this salt for a number of reasons. Apart from the synthetic anti-caking agents and other additives, pure sodium chloride is a highly refined product, as pure NaCl doesn’t exist in nature. Typically derived from either marine sources (e.g. sea salt), or mined from prehistoric salt deposits (e.g. rock salt), natural salts contain a diversity of nutrients including calcium, magnesium and potassium, as well as a host of trace minerals. The net effect is that these natural salts moderate the direct influence of sodium in the body, and because salt craving can often be a sign of a mineral deficiency, helps to address the root cause of nutrient imbalances.

In Āyurveda, there are five basic groups of salt, called the pañca lavaṇa:

• saindhava lavaṇa

• sauvarcala lavaṇa

• viḍa lavaṇa

• sāmudra lavaṇa

• audbhida lavaṇa

Consumed not just as a flavor or condiment, the pañca lavaṇa are viewed as therapeutic agents, used singly or in combination, found in many different formulas used both internally and topically, such as Bhāskaralavaṇa cūrṇa and Saindhavādi taila.

Saindhava lavaṇa is considered to be the best among salts, mined for thousands of years at the feet of the Himalayas in the Sindh region of the subcontinent. It is derived from the ancient Tethys Sea that at one time separated the subcontinent from Asia. Also known as pink salt, sendha namak or Himlayan salt, saindhava is a light-colored rock salt with a mild taste and sweetish-salty flavor. Saindhava is stated to alleviate all three doṣāḥ (doshas), enkindle digestion, restore electrolytes, benefit the eyes, reduce burning sensations, and enhance fertility.

Sauvarcala lavaṇa is another type of rock salt mined in the Sindh regions and elsewhere, but contains significantly higher levels of iron sulfide, providing for its blackish-red color and characteristic sulfurous odor. Also known as black salt, kala namak, sonchal or sanchal, sauvarcala is considered best for digestion and to balance vāta.

Viḍa lavaṇa is an artificially-prepared salt, made by boiling the powders of saindhava, Āmalakī, Harītakī and sarjakṣāra (sodium carbonate) in water until it is completely evaporated. Naturally rich in ammonium chloride, viḍa is black in color, and possesses an alkaline, salty flavor. It is used to correct kapha and vāta, reducing heaviness in the chest and promoting good digestion, and the proper excretion of feces and gas. Viḍa lavaṇa is generally not used for dietary purposes.

Sāmudra lavaṇa is unrefined sea salt, prepared by evaporating off the moisture from seawater. It is made all over the world, and is differentiated from refined salt by containing a high density of trace minerals, giving it a greyish, rather than pure white appearance. It has a mildly warming energy, and acts to enhance digestion, reducing vāta and the expulsion of flatus, and is only slightly aggravating to pitta and kapha when consumed in larger amounts.

Audbhida lavaṇa is a type of salt that is collected and purified from the soil by calcination, and is rich in sodium bicarbonate. It has an alkaline taste and action, and is considered to be difficult to digest, greasy in quality, cold in energy and acts to reduce vāta. It is used therapeutically, but is generally not added to food.